Not Dyslexic but Visually Overloaded: When Letter and Word Confusion Isn’t a Language Problem

When a child consistently confuses "b" and "d" or reads "was" as "saw," the immediate assumption is often dyslexia. Parents schedule evaluations, teachers implement phonological interventions, and everyone focuses on language processing. But what if they are looking at the wrong system entirely?

For a significant number of struggling readers, the problem isn't in how their brain processes sounds and language, it's in how their visual system manages the physical act of reading. These children aren't "dyslexic"; they're visually overloaded.

The Hidden Visual Demands of Reading

Consider what reading actually requires from the visual system. Your eyes must make rapid, precise jumps called saccades across text, roughly four to six times per second. Between these jumps, during brief pauses called fixations lasting just 200-250 milliseconds, your brain must extract visual information, recognize letter shapes, and maintain stable binocular vision.

For skilled readers, approximately 75% of reading time occurs during these fixations, with only 10% spent in the actual eye movements. The remaining 15% involves regressions, backward movements to reread text. A proficient adult reader makes one regression every three or four lines. A struggling reader? Three or four per line.

This isn't a language problem. It's a traffic control problem.

When the Visual System Can't Keep Up

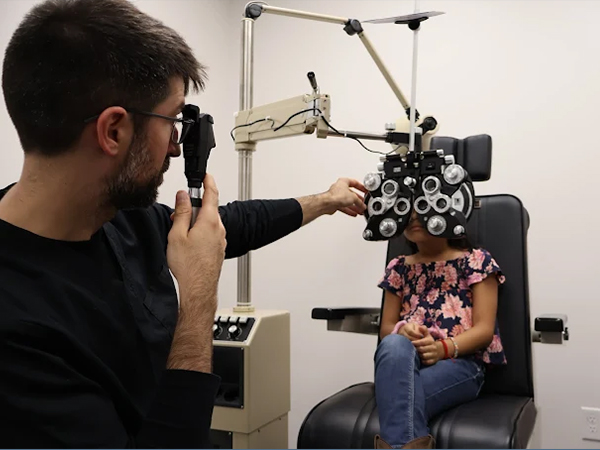

Children with visual processing difficulties face challenges that have nothing to do with phonological awareness or decoding skills. Their struggles stem from foundational visual abilities that many assume are simply "there" if a child passes a basic eye chart test. The critical skills include:

- Eye teaming (binocularity): Both eyes must work together seamlessly. When they don't, children may see double, experience print that appears to blur or jump around, or unconsciously close one eye to reduce confusion. Some children avoid reading entirely because their brain can't integrate two different images into one stable picture.

- Ocular motility: Eyes must move with precision and control. Poor saccadic movements lead to losing one's place, skipping words, or experiencing letters that seem to overlap or run together. These children aren't being careless, their eyes literally cannot navigate the page efficiently.

- Focusing ability: Readers must rapidly shift focus and sustain it. Difficulties with accommodation cause eyestrain, headaches, and fatigue that have nothing to do with comprehension but everything to do with physical discomfort.

- Directional and spatial processing: Understanding that "b" and "d" differ based solely on directionality requires mastery of arbitrary conventions that some children's visual systems struggle to internalize. For these children, the difference based on directionality "does not exist at all", not because of language processing issues, but because their visual-spatial system hasn't yet learned to prioritize these distinctions.

The Misdiagnosis Problem

Here's where confusion often arises: many symptoms of visual processing difficulties overlap with dyslexia. Letter reversals, slow reading speed, poor comprehension, and avoidance behaviors appear in both conditions. However, the underlying mechanisms, and therefore the appropriate interventions, are completely different.

A child with phonological dyslexia struggles to connect sounds to symbols and decode unfamiliar words. Their visual system captures the letters just fine; the breakdown occurs in the language processing network.

A child with visual processing difficulties may have excellent phonological awareness and language skills. Their breakdown occurs earlier in the chain, in capturing, stabilizing, and efficiently scanning the visual information in the first place.

Consider this: if a child's eyes make erratic movements, require excessive fixations, and constantly lose their place, they are going to struggle with comprehension; not because they can't understand the text or decode the words, but because they can't efficiently gather it together in the sequence in which it is printed in front of them. Their brain is so occupied managing the mechanics of seeing that insufficient resources remain for the higher-level task of understanding.

The Role of Development and Experience

These visual skills aren't innate, they're learned through early childhood experiences. Vision develops through interaction with the environment, particularly through activities involving eye-hand coordination, spatial navigation, and visual-motor integration.

Children who've had limited opportunities for these foundational experiences, or whose visual systems develop more slowly, may arrive at school unprepared for the intense visual demands of reading. The classroom environment can place overwhelming stress on an underdeveloped visual system, with up to 80% of tasks demanding visual inspections, discriminations, and interpretations.

Moving Forward: Recognition and Response

The good news? Visual skills can be developed and improved. Research demonstrates that targeted visual training, including exercises for pursuit and saccadic eye movements, focus facility, stereopsis, and binocular coordination, produces measurable improvements in reading performance.

Studies on saccadic training programs show particularly promising results for struggling readers, with some research demonstrating significant improvements in reading fluency and comprehension after just 18 twenty-minute sessions. Children identified as "high-needs" often show the greatest gains, and younger students benefit more than older ones, underscoring the importance of early identification and intervention.

The Bottom Line

When a child struggles with reading, teachers and diagnosticians must look beyond language processing to assess the foundational visual abilities that make reading possible. Not every reading difficulty is "dyslexia", and not every intervention should focus on phonics and phonological awareness. For many children, the path to reading success begins with recognizing that their visual system needs support, not their language system. After all, think about how many millions of children learn to read at home before starting school, without ever having had one single class-day of phonetic instruction. This shows the extent to which harping so intently on phonetic instruction misses the forest for the trees.

By understanding and addressing visual processing difficulties, we can help these children move from visual overload to visual efficiency, transforming reading from an exhausting struggle into an accessible skill.

The question we should be asking isn't just "Can this child decode words?" but "Can this child's visual system effectively capture and process the visual information required for reading?" Sometimes, the most important intervention has nothing to do with language at all.